Saturday, December 30, 2006

Week 15 (Building a Program Management Office)

Pretty amazing thought, but I’ve been noticing just how valuable trust is and how expensive distrust is.

Think about how much easier it is to work and interact with those you trust versus those whom you either distrust or who you just don’t trust as much. I think in the working environment, this can be greatly influenced by the management team. I was fortunate to work in a company where trust was an integral part of the culture and in others where CYA was the norm. I got a lot more work done in the former than the latter.

Trust impacts a lot of areas of your work life. The biggest and most obvious I think is communication. There is a completely different level of communication with those you trust and those you do not trust. Communication with those you trust is often less formal and overall richer in content. You are more likely to have a face to face with those you trust (you probably like them more). Face to face is the richest form of communication; you convey much more than just the words. You can communicate greater range of meaning and emotion.

On the other hand, those you do not trust are more likely than not to get an email. Probably one that has a few cc’s – just in case. The email is likely to be very factual and directive – “I need such and such by Tuesday.” You’re unlikely to convey emotions (emoticons not withstanding) or any richer channels – you probably even avoid verbal communications.

OK, yes I am talking about myself as well. I find that distrust leads to more distrust and avoidance and thus non-communication and ultimately ineffectiveness which hurts everyone and your project. Therefore, I conclude that it is counter-productive to distrust someone – regardless of their prior behavior. So, I can’t remember who said it, but the motto goes “trust, but verify.”

I’m going to work on adopting that. It is unprofessional for me not to verify and ensure that what is committed is done, but at the same time it is unprofessional (and unproductive) for me to go on the assumption that it will not be done, or not done well. I think I will save a lot of time and heartache personally.

Let me suggest then that trust is not earned it is given, and that we should give it freely and constantly to those we work with. Yes, just like Charlie Brown always going for the field goal with Lucy holding the ball. If you are in an un-trusting work relationship, it is time to take the first step – just like I will on Monday.

Week 14 (Building a Program Management Office)

As I look at our projects, we have about 15 months between now and final implementation. We also have all our requirements completed, defined and ready for programming. All this is great, but I’ve been thinking a lot about our ability to make changes (mostly scope) over the remaining time.

In looking at this, the first question is: What is our capacity for change? I think this has to be determined based on resources, schedules, lead times, budgets and the like. We may actually have the capacity to make a 180 degree change, or a series of changes that add up to that. In any case, I think each project must have some “change limit” – this being the amount of change that can be absorbed within the time and budget available.

The first existing method that comes to mind for managing change is the management reserve budget. The intention of this is primarily to deal with risks, but something similar might be arranged for change. Maybe a change reserve budget. This would then define the capacity for change up front and allow us to track against that capacity. I think that we could then add something called a “change rate” to allow us to better allocate that capacity across the project.

The rate of change would naturally (I think) have to decrease over the course of the project. So that while we might have the capacity to make say $100,000 worth of changes, we could not reasonably make all of those changes at once, nor would it be possible to make them all at the last minute.

I think that the rate would have to continually decrease across the duration of the project, and at some point (depending on methodology, flexibility, resources, etc) the project would not be able to sustain any changes - we used to call this “the freeze.” I think then that our change model would look something like that below:

I have not figured out how to determine a good rate, but the idea here is that we pace ourselves with our changes, and that if we try to make too many at any one point, we end up overloading the project- impacting dates, etc.

I know that the traditional model of change control is that we always assess the impact and elevate that to the “powers that be” for a decision on whether we can do the change or not. But experience has shown that we often end up making certain changes and not changing any dates. How many times have you heard “it’s only a week, can’t you absorb that in your 10 month project?” Well yeah, I did absorb the first 12 one-week changes, but this is lucky 13. Now with a “rate” or speed limit, you can schedule the changes, or push back if there is too much at any given time. One way might be to say that we can only accept X amount of changes for the next cycle / month / period.

I think that the concern I am looking to address is the tendency to use up our entire change budget at the beginning of a project and get ½ way through with nothing left. If we use the rate as a limit, then we can actually have the ability to make changes later in the project when they’re needed.

Another idea I hear was about prioritizing changes, I worry about this for the simple reasons that if you only have one change, then it is top priority. Then after you put that in the next change that comes up will be top priority. The priority system is useful when you have all the information in front of you, but with change, you don’t know what is over the horizon. If you did, you would have planned for it and it wouldn’t be a change and you wouldn’t need to prioritize it.

So I think the answer is to pace yourself. Whether you are running a marathon or a sprint, if you use up all your energy too early, you’re in for a hard time. If we use the change rate, then we know we will have the ability to handle at least some part of what is coming.

Of course, I have no idea how to determine a change rate, and as I think more, I realize that this will create a backlog of changes – which we can then prioritize! Hmmm

Thursday, December 14, 2006

PMO Staffing (short)

Staffing is also prime target of politics. Without a project prioritization system, the assignment of project managers can (and often will) be viewed as arbitrary, unfair, or biased. One way to counter this perception is to be scrupulously independent in everything you do. It will not help all the time, but being know as fair and unbiased in the little things will serve you well when it comes time for the big decisions.

Another staffing political pitfall is more subtle. In these situations, one group starts requesting a specific PM. If Joe did well for Accounting in the last project, then they will probably be asking for Joe again. They will hit you with pleas like “he already knows everyone here”, or “he’s familiar with the way we work”, and more. It sounds immanently logical and that’s the trap. Going down this path will turn Joe into “the Accounting PM.” And if Accounting has their very own PM why can’t everyone else? And why isn’t Accounting paying for him? And finally, why doesn’t he just report to accounting and we’ll get rid of the PMO?

So be careful how you staff your projects and keep the long view in mind – someone has to.

Saturday, December 02, 2006

Week 13 (Building a Program Management Office)

This week did once again cause me to think about roles and identities. What is the PMO? What is a project manager? It’s easy to say “it depends”, but when there are people and projects involved, we need to have a clear definition. I have already learned that if there is more than one boss, there is more than one definition of your role. This is doubly true for consultants.

In bringing on the new PM, I am concerned that she is being under (used/appreciated?). In this case, the PM is certainly capable of managing a large part of the project and she could certainly provide some very useful advice and counsel to the leadership team. Because of the perceptions, this is just not likely. The perception is that the PM is there to do the support work, and that’s it. I brought the new PM to the board meeting and I was asked by the business lead why I brought her –as in “she is not this level so she doesn’t need to be here.” This pretty much defined at least our starting point.

Again, it comes down to people and I have a real problem here. Clearly, we (the PMO) were brought on because of our knowledge and experience, yet this is rarely sought and often unwanted. Why would anyone seek a particular set of expertise and then ignore it or leave it on the shelf. It is like buying a high-powered computer and doing nothing but web surfing. Strange, what does this mean? Well I have a theory.

I think that the problem is one of comfort and understanding. Using the high-powered computer example, if all you know is web surfing, then that is what you’ll do. They see the computer as just able to web surf faster and better, and do not see that they can produce multi-media presentations or do their taxes or run a small business – or even better – play the latest graphics-intensive games. So the challenge there is to raise awareness. The second challenge is to make them comfortable with the tools and techniques of project management. So how do I go about that???

Well, first thought is that I have to become more assertive and aggressive. I can’t play a passive and supporting role; I have to take an active and leadership role. And that will certainly piss someone off. I don’t seem to be having a lot of luck in the persuasion department, so I’m going to take some things on myself (more work, but hopefully more success) and I’m going to push for some other things. One of which will be to have full-blown planning session for one of the projects – that could be successful, but not if everyone comes in with a bad attitude – which they will if I do this wrong. Well, this is the time of year when everyone is supposedly in a good mood; maybe I can leverage some of that. Ho Ho Ho.

PMO Support Function (short)

A PMO provides support services to assist with the management of a project. The key differentiator between support and project management is that support is not a managerial role. A supporting team member will often update the schedule, run meetings, follow up on open issues and other similar tasks, but they will not have the responsibility or authority to make project level decisions. Supporting on a project is often a good role for junior PMs, showing them the processes and placing them with a more seasoned PM for mentoring.

Support is the hard part of project management and it is what often meets the most resistance. Team members do not want to take minutes, track issues and action items, produce reports and so on. As with all clouds, this one has a sliver lining and becomes one of the keys gaining project management acceptance.

If you – the PMO – perform the support function, your stakeholders can realize the value of project management without incurring the cost. This will open a lot of doors and minds. Providing exceptional project support then is one of the first steps in building a great PMO.

Friday, November 24, 2006

What's a PMO (short)

Instead, I’m going to suggest that this is the wrong question. The question is not “What is a PMO” but rather “What is YOUR PMO.” While PMOs certainly share common characteristics, those characteristics describe a PMO and do not define it. The only definition that matters is the one you and your stakeholders have created.

Your PMO will serve the needs of your community, your company, your management. Your PMO will be unique and effective within your environment and not a manifestation of some theoretical model out of a textbook. Next time someone asks “What’s a PMO” – tell them about YOUR PMO.

Week 12 (Building a Program Management Office)

The two hour meeting lasted about an hour and fifteen minutes. We had good conversations and discussions. Both projects have made marked improvements over the past two weeks and I think the teams are much more confident and optimistic. That is really half the battle sometimes. At this point, we have a fair handle on performance against milestones and schedule, change control, scope and issues. Not so hot yet on risks, resources, financial performance and a few other areas, but working on it. Since only one department even records time and cost to the project, we are not going to achieve more than a fairly low level of control and information in those areas.

The good news for this week is that we have a project manager starting in one of our locations to help with the project work. Our one office is doing a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of PM work, and it is not getting the attention that it needs. Our new PM will start off with some more administrative and analysis work, but I expect that they will have much more responsibility very quickly. I really look forward to this as I am hoping that it will free some of my time as well so that I can spend more on putting together a PMO guidelines that can be used for all projects of this time. If the company is going to get in this business, then having a method/standard of operations for implementation will be very useful!

Well off to run a few of those new found pounds off. I think 20 miles will do the trick – that would be…. Unlikely . There’s still some apple pie in the fridge…mmmmm

Week 11 (Building a Program Management Office)

Right now, one of the projects is working with our customer and the company that currently holds the contract to negotiate a live date. We had a change in scope and delivery and that caused all three companies to have to look again at the dates. Right now we are in a situation where we each have a date that works for us, so that makes three dates. I am sure after our discussions and negotiations we will come up with a date that is equally unpalatable for all of us. Such is compromise. I’m sure we have not heard the last on all this; it is going to be interesting.

On the other project, we really have a good workable project schedule. Now for the aficionados, no it is not leveled and based lined, with actual times and so on. That, frankly, is a little more than we can really expect based on quite a few things. The schedule does however clearly indicate milestones, major tasks and responsibilities. In other words, what needs to be done when and by whom. We have a bit more than completion dates; we do have durations and hence start dates. Right now, all of the tasks are 80 hours or less, and span two weeks or less, so we have a fine enough level of detail to be able to track the work carefully and elevate and or react as needed. I am not a stickler for the 8 – 80 rule or other such PM rules. If you read this blog much, you know that I oppose rules and forms and procedures that exist only to be complied with. If something doesn’t make life easier/better for the PM and the team then my vote is – forget it.

I had a presentation on Monday that gave me the chance to put together some of the project information in one consolidated format. We don’t have a standard presentation template. I have to confess that I enjoy presentations. I like the idea of putting together information in a format that in some ways can be artistic. If I have not said this before, I highly recommend Edward Tufte. He has some extraordinary examples of information presentation. His books and workshop are worth every penny! He talks about things like information density, sparklines (my favorite). He sums it up well as “simple design, intense content.” Not that my presentation would ever wind up in one of his books, but I am working on it.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Week 10 (Building a Program Management Office)

I had another difficult week this week. We had 2 2-day sessions where we tried to get a better handle on the work for the two projects. We actually made a lot of progress, and I think at least one of the projects is on the right path. Granted the path will be very difficult and busy. We have a lot to do between now and the live date of 3/1/07. I think that the tone of the group is much better now than it has been and I honestly see them as a “team.” I honestly do not know why this group seems to be more of a team than the other project group. I think it is certainly something that I will look at more as the projects go on. The other project group is more a series of teams who are working together. I think that some of it has to do with the size/intensity of the project combined with the personalities and the overall organizational structure.

But first about this week; for the smaller project, I was assigned (volunteered?) to serve as facilitator. The goal was really to get a clear mutual understanding of the work needed to be done between now and the live date. My first step was to lead the team through a very high level breakdown of the project. Nothing really detailed, or down to the work package level. Instead we looked at the high level tasks and looked at the task to see how complex it was, how many dependencies there were, and how “independent” the task was. For most tasks, we did not go into a lot of detailed analysis. We did find one are of tasks that one member of our team nicknamed “the water-main” that represented the critical path and many associated important and highly dependent tasks. While we still have not done any critical path analysis, I am sure that most of these tasks will end up on the critical path, or the resource critical path.

To do the detailed analysis, we went low-tech. We started with the WBS created earlier and stated breaking down the tasks and sequencing them using sticky notes and a whiteboard. I recommend this since you can move the tasks around easily and draw the relationships using the whiteboard and whiteboard markers. Nothing is permanent; you can toss a sticky out if you don’t need it, and you can break it up into two or three sitickies if you need that. This method is very flexible and visual. I think that works for most people. By placing the information on the wall in front of the team, everyone in the room can look at any part of the diagram and any participant can take as much time as they want on any section. This gives each person a lot more freedom and usually a lot more involvement.

Some other conventions we followed for the meeting. We wrote the meeting goals on a poster-sized sticky and it was on the wall and visible the entire time. We had a “parking lot” – another poster-sized sticky where we kept items that we wanted to talk about, but just did not have enough time, or were not directly related to the goals of the meeting. We also had a poster up for risks – here we wrote down risks as they came up during the discussions. I like this method since risks always pop-up during these types of meetings, and if you collect them all and address them at the end, you often find that some of the risks are gone based on what you’ve done during the meeting, and often many can be addressed with the same mitigation plan. The last constant we had was a poster with “to do” or action items on it. This way, when something came up we wrote it down and moved on. At the end of the meeting we went over the to do list, assigned someone to each and a due date. It was a great way to wrap up.

The other 2-day meeting was somewhat similar. I am faced with a very difficult situation in that group where I have somehow earned the enmity of one of the team leads who is working very hard to have me marginalized and / or removed. This is a very difficult and sensitive situation for a consultant. I am not handling this well or badly, somewhere in between, but I am being deliberately cautious and non-confrontational. It is amazing how much different things are when you are on the outside looking in.

Regardless of all that, the meetings went well. That project is certainly in a more difficult situation, and the team members are not as open to compromise and innovation as the other team. The meeting saw a wide use of the “can’t” word and several “shoulds” and “musts.” I think this team could find some creative alternatives to the situations they are in, but the political environment encourages individual success over project success. I have seen this a lot in many different organizations. Simply put, the organization, company, and most importantly the compensation system encourages success within the organizational hierarchy over successes that span organizations. This is often one of the biggest risks that projects face, and one of the easiest to overcome.

There are a lot of ways to improve projects success chances by overcoming some of my thoughts on this are:

- Give someone specific responsibility for project success and give them the money to do this. Asking someone to succeed on a project over which they have no real authority is a huge risk. Make no mistake – money is authority. The person with the funding is the one running the project. The closer the money is to the project, the more likely it will be used for the project only.

- Create an extra-organizational structure (like…. say a PMO) to run the project. The less influenced this group is by the organizations involved, the better. I’ve written on impartiality of a PMO before. I was able to observe over the last few days how much easier it is for the PMO to facilitate a meeting than it is for one of the project teams to do so. In the meetings that I facilitated, the discussions were within the team and there was no thought that I was trying to push the meeting or group towards a solution. In the ones where a team member was leading, there was noticeable tension between team members and the facilitator, and a tendency of the facilitator to move the meeting in a slightly biased direction.

- Create dedicated project teams. I’ve seen this work time and again. Of course it needs to be a TEAM, and it needs to be DEDICATED. That does not mean a few part time people from different areas working together over the phone when they can make their schedules meet. Dedicated team work best when their members are solely dedicated to the project and they are as co-located as possible. If you can have 1 or 2 locations where the majority of the team are that’s a plus. I know this may sound contrary to flat world theory – of which I am an advocate. I still think that collaboration is best done face-to-face. The further apart your team is the less they will collaborate. Face it, to collaborate to the guy next to you often means leaning back in your chair, to do so with the team in India means scheduling a conference call, and trying to get 4 groups in 3 different time zones together is a major effort. It’s not as easy as standing up and yelling – “hey, I’ve got an idea, let’s get a coke and let me bounce it by you.”

And now that I am thirsty, I think I will take my own advice and get something to drink as I – yes, you guessed it – wait on my LATE flight home. Hey maybe that’s why I don’t believe in this dispersed group thing?

Week 9 (Building a Program Management Office)

This week I got a lot more time to do some physical, document producing work. As I’ve mentioned, one of my responsibilities is to organize the work being done by the teams and to create templates and procedures that can be used in future projects that are like this one. I kind of like that part of the work since it is a form of legacy, something that I can leave behind and something that I have the opportunity to create. I’m somewhat challenged trying to spend the kind of time I would like on these activities. Of course, I recognized that this is only one part of the entire job, and that as much as I would like, I cannot loose myself in that, but rather have to continue with the relationships that will ultimately help make the projects successful.

There in lies my newest problem – people. Here is my lesson this week. No matter how innocent a situation appears, do not ever takes sides in an internal argument. No matter how obvious it is that one side or the other is right or justified or whatever, do not take sides. You can agree with someone, but that had better be because of your knowledge or experience and not because you share the opinion. Here is what I did in a nutshell.

I was in a meeting where one member of the meeting showed their frustration and somewhat directly implied that another member was deficient in their duties. So someone got mad and made sure everyone knew it. Nothing huge - I’ve been cursed at, walked out on, hung up on, screamed at .. you name it, and this was nothing of that level, just a clear statement of displeasure with a bit of “I don’t care who knows it.” After the meeting I was called in to comment. I sad that it was clear someone was frustrated and that the behavior was noticeable and antagonistic – and in my opinion it was. I had pretty much forgotten about it but when I was asked that’s what I said. Well that was when the you-know-what hit the fan.

The person I talked to reported my statements to the manager of the person who spoke out. That person called me and quizzed me, and clearly mentioned my comments to the original offender. Well that person has placed me at the top of their hit list. This person is not the type to forgive and forget, nor are they into “proportional response.” My action has caused an all out war against me where this person is probably expending far more effort trying to harm me than in doing the project. In fact that is the project – wonder if there’s a charter or a schedule? Probably not, since project management is unnecessary to hear this person talk.

So the lesson is, if this ever happens to me again, I will politely say that I do not wish to make any comments in relation to this issue. I will say that my personal opinion is not really needed to help the project succeed. I will not be impolite, but I will be insistent and mute. Once again, I learn that no matter how honestly people ask, they do not want to hear my opinion. I already have a rule that when someone asks me a question like “is there something I can improve” or “what do you think of my management style” I always avoid commenting, deflect the conversation or give some innocuous answer. When someone working for me asks for that kind of feedback, I always tell them to think about it and ask me again in 48 hours. Those who really want to know, ask again. This doesn’t mean I don’t give unsolicited feedback where it is warranted, it is solicited feedback that has invariably gotten me in trouble.

Anyway, the week pretty much went OK, I got to spend a lot of time putting together status reports, project schedules and other useful docs. I hope to get them into use the week after next. I also spent a lot of this week getting ready for the planning sessions next week. This is really my first big opportunity to show some of my skills. I think I can lead at least one of the project teams to a good resolution. The other one, well I’m not so sure, too many chiefs and too much politics and too many divergent goals. I’m sure we will get through all that, but it is so unnecessary and counter-productive. As an outsider, I have the opportunity to observe it and learn a great deal. I hope I’m learning how to put it aside in myself and focus on the job and the people.

Saturday, October 28, 2006

Week 7 (Building a Program Management Office)

In spite of everything, we went into the meeting to present the requirements and it was a disaster. Everyone had a different agenda and opinion about the requirements. We discussed AGAIN things that I swore we had resolved. The program managers and I got together and did a quick lessons learned on the whole thing. We discovered what is probably obvious.

The meeting with everyone face-to-face was a great idea and worked well. Other things that we did well were to keep a single list of the requirements and work from that whenever we got together. The consensus was that the communication was good as well, and that everyone on the team was kept up to date on what we were doing and what was decided. And that is it for the good news.

On the lesson side many of the mistakes were mine. Communication to the board was not good or clear, and the board was well behind what the team was doing and needed to be brought up to date before we could give them the current status. I did not keep track of this and start from the last time we talked with the board and moved them to the decisions the team made.

The team did not have consensus going into the meeting and the communication was ad-hoc. We needed to clearly agree on who would talk about which requirements and what each of them would say – hopefully what we all agreed on! If we added an agenda (yes I did not put out an agenda – I could kick myself) with the appropriate information, then it would have been smoother.

I think my take from the whole thing is that I need to be much more formal and complete with any communications to the board. I hope the next one works, I’ve spent some time putting together a presentation for the next meeting – Tuesday’s monthly meeting. As I was doing that I realized we needed a lot better information about our projects. We really don’t have any metrics at all. We do use the red/yellow/green, but it is not as objectively determined as I would like so building metrics is my big goal over the next month.

What I am thinking is keeping it simple with schedule, compliance and goals. We do not really have good project goals. I mean basically we have the “get the job done” goal, but no real way to tell if we are making good progress towards the goal. We can tell that we are working hard, but not that it is on the most important things. I’m going to interview the board to get their goals, aggregate them and set up some criteria that we can check against.

Schedule will be kept simple – on schedule, off, etc. The problem here is that we do not have good schedules. That is what I’m working with the teams on during week 8. I expect that we will have something with milestones, deliverables, and good dates. I’m sure this will help everyone at least have a better picture. I am learning that project schedules are a lot more fiction than reality, but we are going to work on that.

Lastly I’m going to use compliance as a metric. The first metric will be the weekly reports then probably keeping the schedule up to date. Don’t know what else, but I’ll think on this. I normally hate these metrics since they look like tattle-tailing, but I think this is one of the only ways we are going to get the teams to do the work needed to produce the information for metrics. We’ll see wont we?

Week 8 (Building a Program Management Office)

Well, week 8 ends with me sitting in the airport hoping that I’ll make it home in less than 12 hours. You never know. This week was very busy and productive. Ha – my phone just rang with the airline telling me that my 1:35 flight is now scheduled to leave at 2:30 – and so it begins! Well the big lesson this week is communications!

On Monday, I met with the customer most of the day going over the project management documentation, procedures, etc. For the most part we seem to be in synch. The customer has a slightly different model and they are looking for much of the same information, just in different formats or with different names. The primary concern of the customer PM is getting audited by their PMO. I cringe to think about that. I can’t tell you how disappointing it is to me that a PMO has sunk to the level of just making sure everyone fills out the forms correctly. And we wonder how we get a bad name. I’ve been thinking about that – I’ll write more later on how I think we get that way. My communication lesson on Monday was that we all have different names for things, so if you want to stick to your definition, then be prepared for misunderstanding. This lesson was repeated throughout the week.

Tuesday was another long meeting day, really two meetings. One about – yes you guessed it – the requirements. And no we STILL did not get it all worked out, even after 4 hours of meeting. Here the communication problem is relatively simple. We are not documenting and communicating our decisions. There is no central repository or central accountable person. With everyone able to continually discuss alternatives and every discussion interpreted differently and no central source or artifact, most of our calls start out with “I understood this to mean that”, or “I thought we were going to do this”…. No one KNOWS what we’re doing, they just all have their impressions of what they think has been decided. We need to implement a more rigorous requirements process. I’m going to push for formal documents to be distributed, reviewed and approved and once approved sent to change control. I know sounds fundamental, but when you hear about our fracturing problem you’ll understand a little better.

Wednesday reinforced my Monday lesson – one of the biggest barriers to communication is the fallacy of thinking that you somehow posses the “right” definition of a word. I actually heard someone say to another team member – “that is not what it means” referring to a certain word. Let’s say the word was “plan.” One we all have a problem with. How many times have we interchangeably used the words plan and schedule? They have two very different meanings, particularly to those who are familiar with PMI’s definitions. I once tried to explain the difference in the terms and that the thing that was in Microsoft Project was a schedule and not a plan. I was generally ignored and was told that I needed to be more flexible in my thinking. That still sticks a little, but it is essentially correct and I’ve tried to do better. Now, I simply call my .mpp file a schedule and if someone calls it a plan, I don’t correct them or argue.

Back to the problem at hand. If you are going to stick with your definition or your mental model, then be prepared for misunderstandings. One of my favorite quotes goes something like: “never forget that with one miniscule exception, the universe consists entirely of others.” Kind of puts thing in perspective. I also think about accident reports where everyone has a different point of view. I remember one I was in where a guy ran a red light and dinged my car, we pulled over and the guy admitted he had run it, but one of the people on the side of the road said that I had run the light, I was shocked, how could someone see the same thing I did and get it wrong, isn’t the truth universal? Well the truth is, but how we describe it isn’t. I try very hard now to think about what the other person is trying to communicate and not just the words they are using. We work in a very technical and precision oriented culture these days and we use a lot of words that have multiple meanings or nuances. Give the other person the benefit of the doubt. Explain what you are saying from different perspectives and when what the other person says doesn’t make sense, ask. Don’t assume, get to the meaning, and for Pete’s sake stop calling a schedule a plan – that really bugs me.

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Leave Well Enough Alone

Here is what I think they are thinking:

- By restricting the choices, the form is easier to fill out for novice PMs. With limited choices, you can guide the PM through the process without a lot of confusion. I think: With this kind of paint-by-the-numbers, either you have a project that is so simple you should probably not need a risk assessment, or you have the wrong PM. Either accept that you don’t need much of a risk assessment, or get a new PM. This form is not going to fix the problem.

- The restrictions make it easier for the PMO to categorize all the project risks that are happening throughout the company, and maybe steps can be taken to eliminate or mitigate those risks at a higher level. A noble and worthwhile pursuit. I think: Maybe the PMO should do some work. Instead of forcing PMs into neat boxes, maybe the PMO should be looking at the risks as they are – not as they are categorized. Where are the lessons learned? Where is the communication and community of practice to share this information? I think the access database with pie charts and pareto analysis is a lazy approach to the idea of recurring corporate project risk. Do all this, but do not force the PMs to fit it into your box, analyze the risks and find out how the risks categorized themselves. By forcing them into boxes, you risk misunderstanding, mis-categorization and actually fixing the wrong issue.

- The form is being constantly tweaked and improved over time. As the PMO – form owners – learn more they make changes to the forms. Each change is designed to capture more information, or prevent mistakes, or to make it easier to fill out. I think: Leave well enough alone!! Maybe it’s time we started thinking of forms as works of art (although many are hardly that!). Van Gogh did not keep repainting Sunflowers to make it “better.” I think that we would all be a lot better off if we simplified every form and then made it next to impossible to change them. Unfortunately, we end up with PMOs who’s only job is maintenance of forms and methodologies, so we take all that knowledge and expertise and destroy it by forcing these people to come up with every more complicated forms and methodologies. Tell me it’s not true.

So I think we would all be a lot better off if we took all that experience and knowledge and spent it helping people become better project managers than in creating forms and methodologies under the assumption that people are bad project managers. First, no form is going to make a bad PM good. Second, no good PM needs a form designed for a bad PM. So make your forms useful, simple, flexible and few. Spend your time spreading PM knowledge not PM paper.

Saturday, October 07, 2006

Week 6 (Building a Program Management Office)

The group also got together and came up with the next set of requirements. There were a lot, far more than we could do with the time and money available. We did do something that I thought was great in that we cut the list down immediately. Without any more analysis or effort, we now have 20 requirements that we are going to do cost / benefit analysis on. The others we are putting on the table and we’ll look at them after implementation. I think that the sooner you cut scope the better. When trying to complete a project, I think it is best to focus on the smallest possible scope needed for success and if things go well, add to it. Like that will happen! More likely, your scope is too large in any case. I suspect ours is as well, but we are looking at less and we now have a precedent of cutting quickly. We also have broken through a mental barrier about taking things out of the project. I think that as we go forward, the team will be more receptive and understanding of not doing things and will be quicker to cut. That will save time and money of which we have too few. Like all projects.

Got some interesting role clarification on Wednesday. We had our first short board meeting call, and I wanted them to help me understand who the major “players” were on the team(s) and who had responsibility for what. The problem I was having, and many of the team as well, was that often two team members would be trying to accomplish the same thing, or no one was working on something important. Not anything malicious, just a normal situation when a lot of people come together to work on something this complex. So I asked if the board could clarify the roles and responsibilities of the team members reporting direct to them. Well, apparently that is me. I had initially understood my role to be much more consultative than directive, but that is not the case. Very interesting… The nice thing is that I got this charter on a conference call that had just about everyone in it. Most of the board and about 20 other people were in the call, so everyone heard it and I am not having any difficulties in the “authority” area. Now how do we organize?

We have a pretty unique situation, doesn’t everyone? My real challenge is that everyone wants to be included in just about everything. You’ve noticed the number of people we have in requirements gathering and conference calls, that is pretty common. My first reaction is that this is too many to be truly effective. Just because everyone has an opinion does not mean that their opinion is going to make a material difference in the outcome. But how do you tell people that?? For some reason, it either comes off as “you’re not important” or “we don’t care about your opinion.” In an inclusive and people oriented culture, this can be a hard message to get across. Case in point, how many programs of this size have 20 people on a weekly quick status call to the Governance Board? Well I know of one.

My challenge now is to build the next level of management (we’re calling the “program level”). My inclination is to keep this level around the 3 -5 number, but it is looking like I have to make it seven. Already people are asking me to invite them to my weekly program level meeting, which I was hoping would be a good conversation among the leaders, but looks like it may devolve into a free for all. I’m not sure what to do honestly except to crack down a little. Next meeting for the group is Wednesday my thought is to run a highly controlled meeting and disinterest the squatters so they stay out and then maybe the number of people will be reduced so we can get a good and useful conversation going. Then again I may be proven completely wrong – yet again. I guess we will find out won’t we?

On another front, I am making a very deliberate effort to improve my communications to, and relationships with, Board members. I came up with something that might work for me. Since I just though of this on Friday, I’ll wait a while to share. The general idea is to make my communications deliberate and effective. Hopefully, I will build good habits there and be even better at my job.

Week 5 (Building a Program Management Office)

Week 5

Well, this has not been a banner week. It really started off last Friday when I went on vacation and did not attend a conference call. Obviously, I should have been in on the call. I clearly misunderstood what was expected. Of course, I did not find out about any of this until I got back in the office on Monday. My long weekend was spent trekking the Appalachian Trail – in the rain. I was really looking forward to going back to work, wearing something dry, not smelling like dirt and sweat, and sitting down on a chair. All of those hopes came true (except for the sweating thing – after I found out about Friday). This does bring up something about discipline/failure and perspective that might be worth talking about for a minute.

I hate to fail – no really hate it. Now I’m not talking about winning at all costs, I’m talking about the making a mistake kind of failing. Even more, I hate to have someone find out about it. But I was also listening last week to Manager Tools , a podcast that is now a must for me, and I highly recommend that if you are managing a PMO, or anything else for that matter. Outstanding content, and thank you Dina Scott from Controlling Chaos for recommending them. Also another MUST podcast for me.

So getting caught making a mistake is abhorrent to me and is often very debilitating. I have a hard time stopping kicking myself and getting on with things. I did talk to two of my board after missing the meeting, and both expertly and honestly coached me. I HATED it – not that they were doing a bad job, they were perfect – using almost exactly the “feedback” model that Mark and Mike talk about in Manager Tools. But that they needed to use it on ME !! That I had screwed up so much just really got to me. Then I thought – I wonder how many times the people I give feedback/coaching to feel exactly the same way? So this was my first good lesson of the week. Something we all know, but that hit home a little more. I can make mistakes and it is not the end of the world any more than if someone on my team made one. That doesn’t excuse them, and certainly not if I make them again, but if I am to grow and succeed, mistakes are inevitable and boy when someone points them out it does reinforce the lesson.

I said the “first” good lesson this week. The second one is what I am now calling “play to the box seats.” In my career I have been pretty good with my directs and generally with my peers. The problem I have universally had is with my supervisors. I won’t go through my excuses, but I tend to put a lot more demands (unspoken) on my supervisors. I do not communicate with them as well as I would like and I often carry misconceptions around. For the most part I have often behaved as if being a good manager is to do my job and make sure my boss does not have to worry about me. I’ve stressed my independence and ability to get the job done. That’s not enough. Yeah- stinks doesn’t it. The fact is that my supervisors are accountable for what I am doing, and they have much more information and far wider views than I do. They do not always want someone who is off alone doing their own thing even if it is well-aligned, intentioned and generally effective.

What supervisors want is someone who can do all those things AND communicate, relate, understand, cooperate and more - At every level of the company. Sometimes project managers think it is enough to do their project well. Not if you want to play in the big leagues. One mentor I had once told me that after attaining a certain level, everyone in management is “good”, and if you want to rise beyond that level it takes more. One of those things is opening up your horizons, becoming far more people and relationship oriented than task oriented and becoming much more effective.

So what am I going to do? Well I’m starting with inclusion and communication. I set up a monthly call with the board that is an “official” status review of where we are on the program and the program activities. This will be a more formal review and presentation. We also have a weekly ½ hour meeting to address any issues or concerns in a more timely fashion. As I get more organized and involved, we will make this change control and issues calls that I know will be very effective for everyone.

On the PMO side we (the PMO) – which is really just two of us now, myself and a manager who spends about ½ of her time on PMO work – came up with our list of documents and RACI roles and responsibilities. What we chose were:

- Action Items / Issues Log – Log of short term work/assignments/decision

- Risk Log – spreadsheet showing risks and actions/dispositions – long term use

- Change Log – List of changes and their dispositions

(the three above are all in one document / spreadsheet) other official documents are:

- Project Schedule – MS project so far

- Change Control Request – the form the change control is written on – one thing we did add here that I like is that we require information about both the “current state” and the “expected state.” I hope this will stop a lot of questions and confusion.

- Meeting Minutes

- Status Report (one pager)

We are hammering out organization and some of what will be reported at each level, who is responsible, accountable and what Red, Green, Yellow will mean.

The presentation is next week, so we will see how that goes. Also next week, we have our first informal board meeting and a two and ½ day onsite about the next group of requirements. Never a dull moment.

Friday, September 29, 2006

Week 4 (Building a Program Management Office)

I did do some more analysis of the existing documents. What is it about some people and documents???? First, the company has several sets of documentation for projects – corporate PMO, the quality management group, and IT has its CMM documents. There are a few others out there, but those are the main ones. Each group has a very cohesive and useful set of documents and often associated procedures. But why are they so complicated?? Why is there so much information needed to do such simple things? I guess when you give people the job of putting together documentation templates and procedures, they just do not stop. Most of us can put together an action item spreadsheet in 10 minutes. Imagine if that was your job – yikes – 10 minutes of work and you’re on the street? No – why not add links and procedures and notes and more columns and and and…..

Sorry, that was a bit of a rant wasn’t it? I guess it is just so obvious to me why people baulk at Project Management when we walk up to them with a ream of paper and say “if you fill all these out, you’ll be a project manager.” Like that loan guy on the TV commercials with the stack of forms to fill out for loans. Except we will put up with that to buy a house, not to run a project! Funny though isn’t it – the last house I bought was about $125,000 and my project is around $10,000,000 but I’m more willing to fill out the forms for the house. Let’s play with that a moment. I spent about 10 hours over the course of several weeks filling out loan papers and the innumerable legal documents and signing my name about 100 times to buy my house. So if I am willing to spend 10 hours for $125,000 then I should be willing to spend 800 hours for $10,000,000 – yep almost six solid months of filling out forms ! Yet I’ll bet we spend no more than 2 weeks in most projects.

My challenge is to find the “right” amount of useful information that takes an appropriate amount of time and put it into the forms and procedures that everyone can use with the least amount of pain. I am also working on how to organize the reporting structure (not organization / hierarchy so much) in such a way as to spread the work out as much as possible so that each level does only what they need and that information is rolled up to the next level who add what is pertinent there and rolls up, etc. My PMO does not have the staff to handle much work (the PMO being me and one other part-time manager), so we have to spread the burden as much as possible to maximize the value and minimize the pain / cost.

I went back and looked into RACI (Responsibility, Accountability, Consultation, Information) method and I think that will play well here both in relation to forms and procedures. We seem to have a lot of challenges in the roles and responsibilities area so I think I’ll address that first through the reporting, then move to decision making.

Onward.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Week 3 (Building a Program Management Office)

The biggest things this week were the requirements. The team did agree to get together in person (guess who is writing this from the airport) to work out the details. I’m very optimistic about the meeting and the outcome. I will get the chance to facilitate a larger meeting with team members from different sites, and I’ll get to introduce a few tools and techniques.

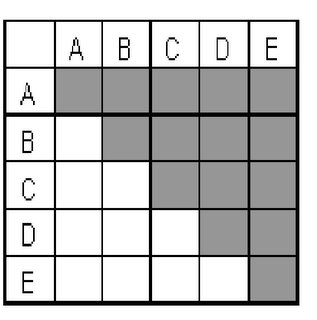

First one will be a forced-ranking system that I’ve used for a variety of purposes from ranking projects to employees. It is a simple paired-comparison process that you can do on a grid. The one I’ll do will be on an excel spreadsheet. Below is a short example of how this works.

The idea is that each alternative is compared once against every other alternative. Half the table is shaded since you are making only one comparison. You can either work down the columns or by rows. Working down the A column, you would ask at each cell - “which is more important A or B, A or C, A or D and so on.” Once you have done this for each row, simple add up the number of times each alternative occurs. The alternative that occurs the most is the most important and so on. In the event of a tie, look for the cell where the tying alternatives were compared – the one selected is the higher. This ends up in a forced ranking with some good indications of the relative importance and differences between the alternatives.

The idea is that each alternative is compared once against every other alternative. Half the table is shaded since you are making only one comparison. You can either work down the columns or by rows. Working down the A column, you would ask at each cell - “which is more important A or B, A or C, A or D and so on.” Once you have done this for each row, simple add up the number of times each alternative occurs. The alternative that occurs the most is the most important and so on. In the event of a tie, look for the cell where the tying alternatives were compared – the one selected is the higher. This ends up in a forced ranking with some good indications of the relative importance and differences between the alternatives.Another tool I’m going to use is a roles and responsibility grid. Pretty simple, but there really is not one for this program.

On the PMO side, I’ve got some work! We have several areas where documents are kept, but they generally are the documents needed by each team, and not a comprehensive set of project documents. There really is not a clear standard for program documentation – there are a lot of suggestions and formats. Our challenge is to set a standard and the appropriate procedures that work within the multiple organizations. I am confident we can do it. I think the roles and responsibilities is the place to start. Understand what is expected of each role, then we can move towards procedures.

Other challenges include Risk management, change management, issue management, and many of the other traditional PM stuff. More and more next week and on.

By the way – never never tempt or challenge the airline gods for they are a vengeful and capricious lot. My flight arrived 2 ½ hours late.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Week 2 (Building a Program Management Office)

Communication: As we all know this is and will continue to be a key. My thought here is that my first job is “seek to understand.” I do not see how I can provide team members with the information that they need without understanding the team members themselves. For this I am convinced that nothing other than personal contact will do the job. I think you may be able to like and work well with people that you know over the phone or email, but that we can’t build the level of trust necessary without a personal relationship.

For this my approach is to do some traveling, probably a lot of traveling over the course of the program. I expect that only by meeting and working directly with the team members will I understand what is important to them and their communication and behavior styles. There is a lot of work involved beyond the traveling. I hate classifying people; we (people) are too complex and too adaptable to be classified. This makes it impossible to me meet once or twice, pigeonhole someone and then stick to that for the length of the program. What I need to do is to “understand” the people I am working with, how they relate to me, the work, the environment, the company, etc.. To do this is going to require that I be very open and vulnerable. I plan to invest a lot of myself in this work, if I didn’t how could I expect anyone to trust me?

Communication is not effective without trust. Trust requires a lot more than a few visits and come handshakes.

Saturday, September 02, 2006

Week 1 (Building a Program Management Office)

The Program is a set of three other programs that each consist of many projects. I’m not sure exactly yet just how many projects there are all told. One of the challenges that I’ve been asked to help with is managing and coordinating all the work so that things do not get dropped “between the cracks” so to speak. There are 6 major separate units involved, 3 are internal (I’ll refer to these as “client” groups), two customers and one external vendor – who works for the customer and us.

One internal organization has a methodology and is following that fairly well. One customer has a methodology and set of documentation that they would like to see, but I have not seen that yet. The client corporation has a methodology that is based on the PMI framework, so it is pretty easy to understand. I am still not too sure if that methodology is in use by all the client organizations.

This week, I mostly just started getting my balance and understanding who is who and what is what. I did get immediately involved in facilitating some work on budget and requirements. As a result of this meeting, I started using Meeting Minutes and Action Items. These were not new to anyone, but I didn’t see any action items for the program initially. I used the client’s forms.

The lesson here I think is to start small and simple. We have one person in the PMO – me, and a methodology consisting of 2 forms. No one seemed overwhelmed or resistant.

Overall the week went well and I got to meet many of the principles. All of whom are very capable and professional people. Nice too, I am looking forward to working with all of them!

Saturday, August 19, 2006

Independence in a Project Management Office

Since being a little self-centered is the norm, your peers will assume that you are operating in the same way. This is a hurdle that you will have to overcome as much as possible in order to effectively do your job. Your PMO will be reporting to someone in some department/division, therefore there will be a perception that the PMO represents that organization. There may also be a perception that the PMO is biased towards that organization. This will be a fact of life that you will either have to overcome or accept. If we use a risk model, this is a risk that you have to choose how to deal with. My proposal is that we deal with it through mitigation strategies.

Get a clear understanding with your manager. Your manager can torpedo any efforts you make towards independence, so it is vital that you have a complete meeting of the minds. If you and your manager agree that independence is important, then you can create a working relationship where it is OK to say no to your boss. A very tricky proposition, but if you have the right information, understanding and relationship, then this can be done to everyone’s benefit. With external decision criteria, and consistency on your part, this can be done.

Become totally transparent. I say totally, the only exceptions that I would make would be for something confidential or legal. In those cases, it is important that you make it clear that you are not sharing the information for those reasons. Most people can respect and understand that. By making all other information about what you do and how you do it available, you show that the Project Management Office has nothing to hide and that there are no secret negotiations going on. This strategy will also help immensely in building up trust. Believe me, people will know if you are hiding something, and if they find out, they will loose faith in you, and that can be the kiss of death.

Fight for those outside your organization. Now, this can’t be fake or contrived. Let’s say that your PMO is reporting to the COO and Marking has a big project that they are having trouble getting resource for. You will want to support Marketing, and actively push to find those people. If this means going to the COO and getting her to take people of her projects to work on the Marketing one, then so much the better. If you support only your own projects, you will not be seen as objective and independent.

Be consistent. In everything, people can not easily trust someone who they perceive as inconsistent. If you combine consistency with transparency, then people will be able to tell why you supported one project over another. They will also see that this applies no matter whose project it is. We all trust predictability. Consistency can also help eliminate conflict before it starts. If people know how you will react, and why, they will often alter their behavior. If someone is trying to get a project through that has a very low IRR, and they know that IRR is one of the top project scoring criteria, then they are more likely to delay, defer or reject the project before it ever comes before a review board.

Stick to you values. I know this is obvious too, but has to be said. Your PMO will have a set of values and goals and behavior (if you don’t have these now, they I strongly suggest that you build them). If you unflinchingly stick to these then you will be seen as trustworthy and independent.

It would be great if you could do all this one time, but unfortunately you will have to constantly engage in these activities. It is like rowing upstream, the minute you stop rowing, you will start going backwards. Sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly, but it is inevitable. If you remain honest and true to your values, then you can make wonderful progress and may begin implementing some very large changes within your company.

Monday, August 14, 2006

Soldiers

Sorry for being out, between contracts, vacation and my laptop being in the shop, things got a little hectic. I want to continue with the discussion of heroes and soldiers. I think we all agree we would like to have a hero around when we need one, but that a team of heroes can be a little – shall we say “sub-optimal.” On the other hand, a team of soldiers can really accomplish anything.

Soldiers

When I refer to soldiers, I am not talking about clones or mindless robots that follow orders to the letter and sacrifice themselves in droves at the whim of their commanders. No, the soldier I am talking about is the professional soldier. Think Roman Legionary or any of today’s highly trained military. With proper management, diversity and organization, a Project Management Office built with good soldiers will be very effective in changing and sustaining a culture of project management. That said, our soldier type has some characteristics that we want to be aware of.

- Soldiers are disciplined: This is one of the main differences between a soldier and a hero. A soldier can be expected to show restraint, paint within the lines and to follow company policies and norms. While a hero will often play “bull in a china shop”, your soldier is unlikely to leave a trail of broken dishes or irate coworkers.

Soldiers are team players: Soldiers work well in units. There is a real synergy when a team of soldiers gets together to tackle a problem. Here is where you will really see the power of teamwork. - Soldiers are Professional: Soldiers understand the company dress code. They understand and abide by corporate behavior norms. Soldiers approach their work as a craftsman would, seeking to do the best they can and with an effective combination of enthusiasm and thought.

- Soldiers are reliable: This probably sounds a little boring, but as a director, you understand the need for reliability. Soldiers help you provide a consistent level of quality in all things. When you send one to a customer site, you know how they will behave, you know they will not say or do anything outrageous, you know they will represent the Project Management Office faithfully. This is vital to creating a trustworthy image and perception of your PMO.

- Soldiers often Specialize: Many of your team will have an area that they are particularly good at. You may have a methodologist, or a trainer, or a mentor, each of us has different gifts and hopefully you will help your team develop those to everyone’s benefit. A specialized soldier working in their realm is about as good as anyone ever gets. This person is “in the zone.”

- Soldiers can be slow: As a rule, your soldiers will usually take a little more time to complete the work, or to address the problem than a hero would. If speed is your only criteria, calling up your soldier may not be the best option. Of course this is not true of all soldiers or all situations. A specialized soldier in her discipline can be as fast as or faster than any hero. Get the soldier out of their specialty, and things slow down a bit.

- Soldiers can be rigid: I am sure you have run into this. The team member knows how to do something, and does it just that way or they look at every problem the same way. To a hammer, everything looks like a nail right? This can be a real drawback when you are trying to institute widespread change. Inflexibility in your team does not set a good precedent or example for others to follow.

- Soldiers can be unimaginative: This goes hand in hand with rigid in some ways. Often soldiers are so good at working within the norms that they cannot see outside them. This gives a limited point of view with limited options. Many times these team members will talk about things in terms of “Right” and “Wrong” – with caps. Once that mind frame is set, it can be very difficult to break out to new ways of looking at things.

The Soldier Culture

In a corporation that has gone too far into the soldier culture tends to be very rigid and is all about following orders and procedures. These are by the book types of cultures to whom rules are paramount. As an example, I recently attended a convention for which I pre-registered. I went to the line to get my materials, and right next to me was someone handing out lanyards – I know I have millions of them, but she was handing out ones that had the convention name on them and all the packet had was the typical string ones. I asked her for one of the lanyards; she asked to see my badge; I showed it to her and she replied that the lanyards were only for the people who were registering onsite. I of course said – “you’re kidding right, it’s just a lanyard.” To which this obedient unimaginative soldier answered “no.” Mindy you she must have been holding 100 of these things. Her customer service ethic alone was abominable. But think from her perspective – she was told that she was to hand out lanyards to the people who registered for the convention on site. I didn’t so I did not get a lanyard. This is the kind of thinking that can pervade the typical soldier culture.

In these soldier cultures, the Project Management Office often becomes little more than forms police or methodology Nazis. While this may be comfortable for some, count me out. So what works?

The Warrior Culture

What is too frequent today is a conflict between the heroes and the soldiers. Soldiers call the heroes “loose cannons” or “cowboys” and heroes call the soldiers “pencil necks” or “suits.” They both see their way as the “right” way, so someone not working the “right” way is “wrong.” This fundamental assumption is the problem. I have a button that says “I’m right and you disagree so you must be wrong.” When this happens, any movement away from “right” is seen as compromise or worse. Guess what, there are a LOT of ways to do things. If there was a right way to build a car, there would be only one type of car, or house, or city, or family…. Take a look around, nature has the idea – diversity, synergy, cooperation.

The best (not right) organizations will have a good combination of heroes and soldiers along with the associated mindsets. You can have heroes that follow rules or soldiers that act independently in unfamiliar situations. Let’s call this the Warrior culture. The Warrior team is capable of organizing and attacking situations with the flexibility of heroes and the discipline of soldiers. Now that is where I want to work – challenge and stability, known and unknown, chaos and order.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Hiatus

I apologize for the recent gap in my posting. My laptop has been sent to the shop, and not only is this where my materials are, but the rest of my family has been active on our only other machine. Who would have thought, now I'm wishing we had another computer - more computers than TVs or bathrooms. I wonder what that says about me......

Back soon

Derry

Friday, July 14, 2006

Marketing Your PMO - Positioning Project Management

With that as segue; I want to talk a little about the shameless promotion of the PMO and Project Management. Personally, I am not very good at this, but this is an essential part of your job as director. You are trying to institute a change in your company and the name of that change is Project Management. Even if you have a fairly fertile environment and a high maturity level, you still have to get out there and talk it up.

How many of you just said “yech?” Believe me I understand; Project Management is a good thing, that’s obvious right. All we should have to do is demonstrate success and everyone will see and want to implement Project Management immediately. As we internet geeks say – ROFL. For the most part, people will attribute your success to you, luck or some other factor. This is not to say that they do not appreciate it or harbor any ill-will to you.

We have been taught from the beginning that success is achieved through hard work, skill, perseverance and sometimes luck. When is the last time someone thanked a process for their success? OK, except for those infomercials that show you how to make millions in real-estate or surfing the internet. In our minds, success is a personal thing; even group successes are achieved through the personal contributions of the team members. We’ve grown up with great personal examples of success - heroes. This is another reason why the Hero Culture (see my July 3rd entry) is so prevalent. Admittedly, it’s not a bad thing for you to be associated with success, what you want to do is leverage the success to show people how Project Management can help them achieve success as well.

What you’re up against

Here is an example of the mental barriers you will face. Take a look at how computers are used. Today it is generally recognized that most workers can and do benefit from the use of computers. In particular, office workers get more work done with higher accuracy and in less time. (Of course we are now expected to do twice as much work in half the time). When mainframe computers and later personal computers came on the scene, they were widely resisted. There were still plenty of people doing their spreadsheets with calculators and typing memos on typewriters. Computers did not achieve success, they enable success. They were a lever that enabled people to do more, better, faster. Project Management is the same thing.

Position Project Management as an Enabler

When you talk about the successful completion of projects, spread the credit wide and excessively to every person involved. With this praise throw in phrases like “our PM processes enabled the team to identify and resolve issues before they became critical.” or “PM helped team members focus their efforts on the critical features that we delivered on-time on-budget.” And so on. If you can get any quotes from people – get them and publish them. Don’t force anything, you do not want false testimonials, you want something that the team members will repeat in 6 months without you around. The message here is that success does come from hard work AND Project Management gives you an advantage.

Position Project Management as a Tool

This is kind of an enabler too, but you will want to use the work tool, or toolkit. This model may work better for some people than the less tangible enabler model. In this case, you would rephrase the quotes above to something like: “Team members used the Critical Items log to ensure that they delivered the greatest value.” Not a great one, but you get the idea. An analogy here that I’ve use a lot is that you can hammer in a nail with a rock, a hammer, or a nail gun. We are tool users who are always seeking better tools, when you position PM as a tool, your message will resonate well.

Position Project Management as a Time-Saver

Personally, I like to position PM as a time-saver. My thought is that when you do a project, you will do the PM process one way or another. You will have to know what your issues are, you will have to know due dates, costs, resources, etc. You can either spend your time creating a method with each project, or you can use one that is proven to work, and change it as needed to meet your needs. So the quotes here are “the team saved significant time by prioritizing tasks using the Critical Items Log.”

Ultimately, you want to look for every opportunity to promote PM, but to promote different aspects and capabilities. You know your culture and the people you work with, some approaches will resonate, others will not. Part of your job will be to find this out and change your message to be meaningful. Don’t think that this ever ends, you will want to keep trying new avenues of communication and messages as things will constantly change and you will need to adapt – but you knew that!

Monday, July 03, 2006

Heroes and Soldiers

I want to talk about two of the many types of people you will work with. As with any attempt to categorize people, my examples will fall short of illustrating the true complexity of people. However, I hope this will be helpful when you are looking for candidates and trying to understand some of the motivations others (and maybe yourself). I know that these terms may raise some controversy for those of you in the states; I am using the archetypes here and not trying to make any judgment or inference.

Heroes

We all know who these are, from Beowulf to Superman these are the people who slay the dragons and save the day. This is the “go to” person who can always solve the problem that no one else can deal with. Heroes live for the impossible task, the life-or-death struggle and the insurmountable challenge. Many of us probably were heroes at one time, getting juiced by the challenge, long hours and impossible odds and finally pulling it off at the last minute. We all love heroes, but everyone is not a hero, and sometimes you just don’t need a hero. Heroes have some characteristics that we need to understand whenever we work with them:

- Heroes are responsive: Pick up the red phone, turn on the Bat-signal, yell for help and your hero is there.

- Heroes get the job done (whatever it takes): If it absolutely, positively has to be done, then a hero will get it done. Great, but pull out your checkbook, heroes do not come cheap.

- Heroes are Fast: Faster than a speeding bullet! A hero will be there, solve the problem and make everything right in a flash – there is no comic hero called “slow man” or “the Slug”, heroes fly to the rescue, they don’t walk.

- Heroes are loners: The only place you will find a team of heroes is in the comics. Heroes don’t want to be bothered with others – sometimes they have a side-kick or trainee, but that’s often a dangerous job. To paraphrase “Q” from Star Trek Next Generation – “it’s hard to be a team player when you’re omnipotent.”

- Heroes make a mess: When Superman battles it out with giant robot invaders, they usually tumble a city block or two causing billions in damages. Ever see a hero cleaning up afterward? No, they are gone on to the next crisis. This happens a lot in programming where the hero comes in and writes some obtuse code that invariably fails 3 months later.

- Heroes are direct: Heroes act on problems, they “go for the jugular”, they are “can do” people who are “results-oriented.” Heroes go straight to the problem and solve it.

- Heroes need contests (conflict): A bored hero will find a dragon to slay, princess to rescue or go on a grail quest. Simple tasks like farming or filling out a timesheet are beneath them, not worth their talents. Without a test of their talents, heroes are not heroes, they are just like you or I so a hero will always be looking for the next dragon or quest.

- Heroes are egotistical: Some exceptions with reluctant heroes, but for the most part, these people are good and they know it. This means that they will have special needs that you will have to meet.

- Heroes are lousy leaders: While a hero may lead a charge up the hill or be the first to attack a problem, they are not leaders. A hero is a terrible mentor. Heroes are not generally patient or circumspect or thoughtful. Heroes act, they do not talk or think or plan.

- Heroes ride off into the sunset: Let me beat these clichés to death. A hero leaves, they’re off to the next challenge, and they often leave a mess. Guess who gets to clean that up?

- Heroes are dangerous: Just ask every Security officer on the Enterprise (red shirts). Standing too close to a hero can be a problem; our hero may be impervious to nuclear weapons, but those of us nearby are slightly less durable. When a hero comes in to save your project, if they succeed, they’re the hero (again). If they fail you will be watching them ride off into the sunset while you clean up the mess and count the cost.

Sounds like I am against heroes. I am not against individuals who are heroic, I am opposed to hero cultures.

The Hero Culture

This is an organization that worships heroes. In these, everything is an emergency; it is all about getting it done and not about planning. Thinking is looked on as ineffectual since doing is paramount. In these organizations, there is always another fire to run to, another urgent problem to solve. People in these organizations are seen as heroes and only those who put forth heroic effort are viewed as valuable.

Unfortunately, this culture thrives on these situations. It is far more exciting to pull the project out at the last minute by pulling 90 hour weeks than it is to just plan the work correctly and finish on time with no fuss. In a heroic culture, the latter type of project is looked on as if there was a failure. Projects that do not require heroic effort must have been underestimated and the team members were lazy. Think about a football game. Who is the bigger hero, the team that puts 7 points on the board every quarter and shuts out the opponents or the one who wins in the last 10 seconds by a hail-Mary pass?

Problem is – projects are not contests, they are projects, and that is where the hero culture fails.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

PMO Overboard